What is vocal fold paralysis?

Vocal fold paralysis is immobility of a vocal fold because of damage or dysfunction of its principal nerve. This nerve travels from the brain, down the neck and into the chest, before turning upwards back to the larynx. Because it passes through the neck twice, it is called the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The left-sided nerve is longer than the right and dips lower into the chest, so it is more prone to injury. As a result, the left vocal fold is about twice as likely to be paralyzed as the right.

Vocal fold paralysis can be unilateral (one-sided) or bilateral (two-sided). Because unilateral and bilateral paralyses have slightly different causes, and very different symptoms and treatments, they are best considered separately.

What causes unilateral vocal fold paralysis?

Most unilateral paralysis of the vocal folds happens for one of three reasons: nerve injury during a number of common surgeries, pressure on the nerve (for instance from a tumor growing next to it), or inflammation that stops the nerve from working (usually attributed to viral infection). Together, these three scenarios account for more than 85% of cases of paralyzed vocal folds. There are dozens of other less common causes, like stroke and other neurologic disease, and side effects of certain drugs and toxins.

Vocal fold paralysis may be an inadvertent result of several common surgeries, listed below. These include heart and lung operations, because the principal nerve of the vocal folds (recurrent laryngeal nerve) dips into the chest before returning to the larynx. Paralysis of the vocal fold is not necessarily a sign that the nerve has been cut. The nerve may also stop working if stretched or squeezed, and sometimes after surprisingly little handling. Finally, branches of the nerve may also be damaged by the breathing tube put in for general anesthesia.

Surgeries that may result in vocal fold paralysis include:

- Thyroid and parathyroid gland surgery

- Carotid endarterectomy

- Cardiac surgery (especially aortic valve surgery)

- Repair of aortic aneurysms in the chest

- Mediastinoscopy

- Thymectomy

- Esophagectomy

- Lung surgery (particularly on the left)

- Cervical spine surgery (anterior cervical discectomy/fusion)

- Brain and skull base surgery for aneurysm or tumor

In cases of paralysis in persons who have not had any of the above procedures, tumors are the most serious concern, with health consequences that reach far beyond voice. Radiologic studies that look over the entire path of the nerves to the larynx, including the chest, are essential. The consensus is that a CT (or CAT) scan of the neck and chest with contrast dye is the minimum study required to examine the nerves adequately when the vocal fold is immobile. Lung cancers are the most common tumors to cause vocal fold paralysis.

In some 15-20% of cases, no reason is found for the vocal fold paralysis, even after appropriate radiologic studies. These are called idiopathic, and usually attributed to viral inflammation. It is important to understand that this is only an assumption.

Finding a cause for a paralyzed vocal fold can be simple, as in hoarseness that occurs immediately after neck surgery, or very challenging. A meticulous history is the most important element in this search, aided by appropriate scans, which include the chest. A diagnosis of idiopathic vocal fold can only be made after all other possibilities have been eliminated.

Finding a cause for paralyzed vocal folds can be simple - as in a case where symptoms begin immediately after thyroid surgery - or very challenging. A meticulous history is the most important element in this search, aided by appropriate scans. A diagnosis of idiopathic vocal fold paralysis can only be made after all other possibilities have been eliminated.

What are the symptoms of unilateral vocal fold paralysis?

In unilateral paralysis, the vocal folds are unable to close, which causes voice and swallowing problems. The voice is hoarse, breathy and soft, and speaking above background noise is a challenge. The pitch of the voice usually becomes difficult to control. Patients get winded when speaking, because so much air escapes through vocal folds that do not close during voicing. This is commonly mistaken, by both doctors and patients, for shortness of breath caused by a lung problem. Sometimes, muscles not usually involved in voicing will try to bring the vocal folds together, which can induce a sore neck after prolonged speaking. Occasionally, voice changes will be accompanied by coughing when swallowing. This is especially noticeable when drinking liquids.

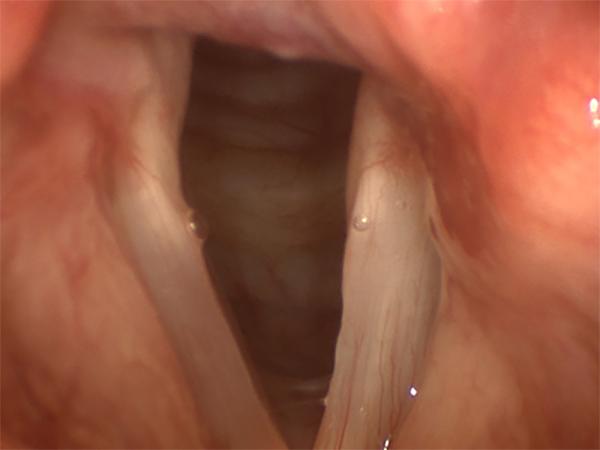

The right vocal fold in this image was paralyzed after a lung operation. This is the typical appearance of a paralyzed vocal fold during quiet breathing.

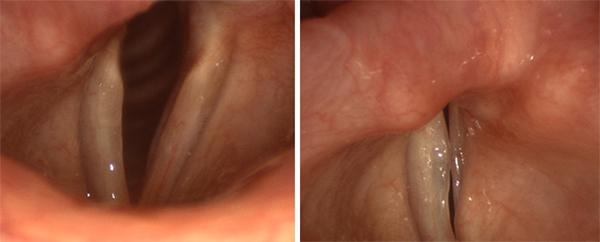

The vocal folds on the left of both images above are paralyzed. Even with extreme effort, they cannot meet their opposing partners.

What does unilateral vocal fold paralysis look like?

Vocal fold paralysis is diagnosed by a lack of movement in a vocal fold. Sometimes this is obvious, but the activity of neighboring muscles may occasionally give the illusion of vocal fold motion. Putting the larynx through a series of motions such as repeated voicing and sniffing will usually clear up any confusion.

In recent years, it has become clear that vocal folds may be only partially paralyzed. This is called “paresis”, and because the vocal fold retains some ability to move, can be especially challenging to diagnose. Vocal fold paresis is one of the most commonly overlooked diagnoses in laryngology.

In this patient with longstanding vocal fold paralysis, the paralyzed vocal fold has lost muscle mass, and become thin and atrophic.

How is unilateral vocal fold paralysis treated?

Some cases of vocal fold paralysis recover by themselves. Neither resting the voice nor exercising the vocal folds has been shown to have any significant effect on recovery. Similarly, no medicine has been proven to help, though some otolaryngologists will prescribe steroids in the belief that they reduce inflammation that has caused the nerve to stop working. While waiting for the nerve to recover, voice therapy is recommended.

Many otolaryngologists recommend waiting six months to a year to allow for vocal fold paralysis to clear up on its own before performing corrective surgery. This interval of time is determined largely by tradition – there is almost no evidence to support this practice. The appropriate interval should be determined individually in each case, based on the extent of disability, likelihood of recovery and vocal demand.

Some physicians have found a test known as electromyography (EMG) to be useful, both to diagnose paralysis and help determine how likely it is that it will recover on its own. EMG is performed by placing needles into the muscles of the larynx through the skin of the neck for a few minutes to record electrical activity. EMG results do not always contain straightforward, “yes-or-no type" information, but they are often helpful in making subtle diagnoses and treatment decisions.

In most cases of unilateral vocal fold paralysis, it is possible to restore near-normal conversation voice, even though, so far, it has not been possible to restore motion to an immobile vocal fold. Treatment is based on repositioning the immobile vocal fold closer to its partner. This is known as medialization. In brief, this is accomplished by injecting the vocal fold with one of a number of available substances (injection augmentation), or by placing a block of artificial material into the larynx through an operation on the outside of the neck (medialization laryngoplasty). Sometimes, this second procedure also involves repositioning the laryngeal cartilages. Each technique has its own advantages and disadvantages, and making an intelligent choice among available treatments depends on discussing these in detail with your physician.

Teflon™ paste was once commonly injected into the vocal folds for vocal fold paralysis. Teflon™ has been found to cause a destructive process known as "foreign body granuloma", which usually has to be surgically removed. For this reason, it has been abandoned by most laryngologists.