What is vocal fold paralysis?

Vocal fold paralysis is immobility of a vocal fold because of damage or dysfunction of its principal nerve. This nerve travels from the brain, down the neck and into the chest, before turning upwards back to the larynx. Because it passes through the neck twice, it is called the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The left-sided nerve is longer than the right and dips lower into the chest, so it is more prone to injury. As a result, the left vocal fold is about twice as likely to be paralyzed as the right.

Vocal fold paralysis can be unilateral (one-sided) or bilateral (two-sided). Because unilateral and bilateral paralyses have slightly different causes, and very different symptoms and treatments, they are best considered separately.

What causes bilateral vocal fold paralysis?

Bilateral paralysis of the vocal folds usually happens for one of four reasons: nerve injury during a number of common surgeries, pressure on the nerves from a tumor growing next to them, stroke or other brain injury, or inflammation that stops the nerves from working (usually attributed to viral infection). There are dozens of other less common causes.

Bilateral vocal fold paralysis may be an inadvertent result of surgery - most commonly thyroid surgery. Paralysis of the vocal fold is not necessarily a sign that the nerve has been cut. The nerve may stop working if stretched or squeezed, and sometimes after surprisingly little handling. For this reason a vocal fold may be paralyzed after even the most uneventful of operations. Another circumstance that must be explored is the possibility of vocal folds being scarred in place from breathing tube damage, rather than paralyzed. Electromyography (see below) can be helpful in this.

In cases of paralysis in persons who have not had surgery or a breathing tube, tumors are the most serious concern, with health consequences that reach far beyond voice. Radiologic studies that look over the entire path of the nerves to the larynx, including the chest, are essential. The consensus is that a CT (or CAT) scan with contrast dye is the best way to examine the nerves in the neck and chest. Bilateral paralysis is more likely than unilateral paralysis to be related to stroke or other neurological disease, so a brain scan may be useful as well.

In some cases, no reason is found for the vocal fold paralysis, even after appropriate radiologic studies. These are called idiopathic, and usually attributed to viral inflammation. These cannot technically be proven, and so it is important to understand that this is only an assumption. Finding a cause for paralyzed vocal folds can be simple - as in a case where symptoms begin immediately after thyroid surgery - or very challenging. A meticulous history is the most important element in this search, aided by appropriate scans. A diagnosis of idiopathic vocal fold paralysis can only be made after all other possibilities have been eliminated.

What are the symptoms of bilateral vocal fold paralysis?

In bilateral vocal fold paralysis, the vocal folds are unable to open, which causes narrowing and blockage of the airway. The amount of space left between the immobile vocal folds determines the degree of the blockage. There is almost always noisy breathing and breathlessness during activity. Sometimes, this is mistaken for asthma by both physicians and patients, which is a dangerous mistake, for bilateral vocal fold paralysis has a very real chance of causing a life-threatening blockage of the airway. Two scenarios in which this may happen are: in cases with bilateral vocal fold paralysis that occurs unexpectedly following a surgery, and in cases with additional swelling of the vocal folds, as during a common cold, that blocks the remaining airway in somebody with a known or unknown bilateral paralysis.

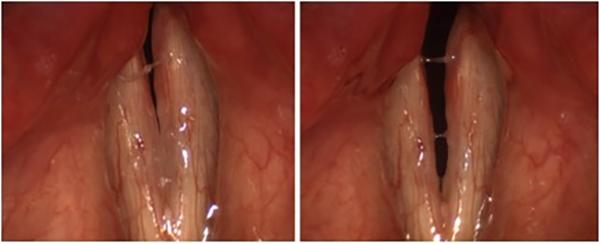

These images show the full range of motion of the vocal folds in a patient with bilateral vocal fold paralysis after thyroid surgery. The folds are closed for voicing at left, and open for breathing at right.

What does bilateral vocal fold paralysis look like?

Vocal fold paralysis is diagnosed by a lack of movement in both vocal folds. Usually this is obvious, but the activity of neighboring muscles may occasionally give the illusion of vocal fold motion. Putting the larynx through a series of motions, such as repeated voicing and sniffing, will usually clear up any confusion.

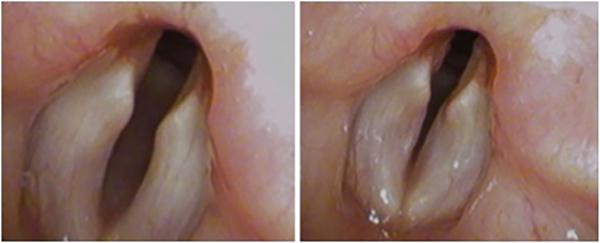

Patients with bilateral vocal fold palsy have less trouble breathing out (left) than in (right). The suction of inhalation draws paralyzed vocal folds together, narrowing the airway and increasing obstruction.

How is bilateral vocal fold paralysis treated?

Initial (and sometimes, emergency) treatment of bilateral paralysis is aimed at making sure the airway will not be blocked. This requires a tracheostomy, which is the creation of a surgical opening from the skin to the trachea. Subsequently, some cases of paralysis recover by themselves. Neither resting the voice nor exercising the vocal folds have been shown to have any effect on recovery. Similarly, no medicine has been proven to help, though some otolaryngologists will prescribe steroids in the belief that they reduce the inflammation that has caused the nerve to stop working. In the event that the paralysis recovers, the tracheostomy is reversible.

Some physicians have found electromyography (EMG) to be useful, both to diagnose paralysis and to help determine how likely it is that it will recover on its own. EMG is performed by placing needles into the muscles of the larynx though the skin of the neck for a few minutes to record electrical activity. EMG results do not always contain straightforward “yes-or-no type" information, but they are often very helpful in making subtle diagnoses and treatment decisions.

If the vocal folds do not recover motion, it is possible to continue indefinitely with a tracheostomy to ensure the airway is open. Removing the tracheostomy, however, requires that the airway be widened, most commonly by surgically removing a part of the vocal fold. This is an irreversible procedure, which may worsen voice and swallowing, and so should be considered carefully.

In rare cases, people with two paralyzed vocal folds live for some time without tracheostomy, generally because they have not been aware of the condition. Even in these instances, living without a tracheostomy is not necessarily safe. The degree of risk should be discussed with your physician in order to make an informed choice.